Across China: China taps digital tech to save thousand-year-old cliff inscriptions

Source: Xinhua

Editor: huaxia

2025-05-10 14:03:45

People visit Wuxi's digital museum in Yongzhou City, central China's Hunan Province, Dec. 6, 2024. (Xinhua/Liu Wangmin)

by Xinhua writers Zhang Yunlong, Zhang Ge

CHANGSHA, May 10 (Xinhua) -- On a cliffside in southern China, ancient inscriptions weathered by more than 1,000 years are being rediscovered -- not with chisels, but with code.

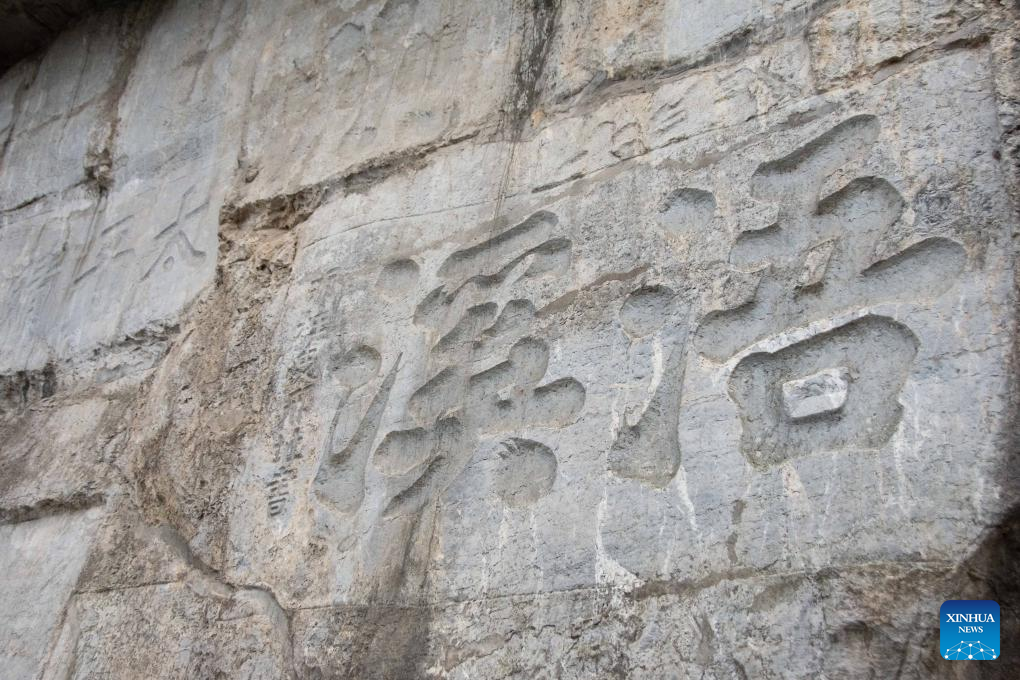

The Wuxi Stele Forest in Yongzhou, Hunan Province, is one of China's most remarkable open-air repositories of carved texts. Over 500 inscriptions, etched into cliff faces and stone tablets from the Tang Dynasty (618-907) through the early 20th century, bear witness to centuries of poetry, politics, and devotion to the art of the written word.

At the heart of the site stands the inscription of the "Da Tang Zhong Xing Song" (literally "Ode to the Restoration of the Great Tang Dynasty"), originally composed in 761 by poet Yuan Jie. At Yuan's invitation, master calligrapher Yan Zhenqing transcribed the text in 771 for engraving on the cliff face. The result -- celebrated for its brilliant prose, masterful calligraphy, and the exceptional quality of the cliff stone -- has been revered for centuries as an example of the "Three Perfections" among cliff inscriptions.

That inscription proved catalytic. For more than a millennium, inspired by Wuxi's dramatic scenery and the cultural gravity of the Ode, scholars, poets and officials continued to leave behind verse and commentary carved into the surrounding rock. Together, they created a layered archive of Chinese intellectual and aesthetic history.

But Wuxi's stone heritage is under threat. After centuries of exposure to wind, rain and biological erosion, many of the inscriptions have faded into near invisibility. For conservators, the task to preserve what remains and recover what has already slipped from sight has become urgent.

Now, a team of digital preservationists in Changsha is leading the effort. Under the title "Revitalizing China's Stone Inscriptions through Digitization," the project is giving new life to Wuxi's weatherworn texts.

"When an inscription that once looked like a faint shadow suddenly becomes legible again, it feels as if we've traveled back hundreds of years," said Kong Hao, who leads the Wuxi stele digitization project and was born in the 1990s. "You can almost see ancient scholars and poets brushing their words onto the cliff face."

Her team uses specialized imaging equipment to capture each stele from dozens of angles, then layers the data using computer vision and processing power to reconstruct even the most fragile traces. "As long as the carved strokes are deeper than 0.01 millimeters," she said, "we believe we can recover them."

Details that had long vanished to the naked eye -- fragments of characters, fading stroke lines, the rhythm of a master's hand -- are now reappearing on-screen, frame by frame. They are entering a growing digital archive designed for both research and creative reuse.

The project is not only reviving what was fading, but also reimagining how people engage with it.

A WeChat mini program, "Digital Wuxi," allows users to trace calligraphy strokes, explore historical annotations, and take virtual tours of the site.

At the on-site digital museum, visitors can browse digitally enhanced replicas of the site's steles, try simulated stone carving, interact with a digital Yuan Jie, and visit a gift shop featuring 3D-printed mementos. The museum has become a popular destination for families and students.

"Through digital preservation, the 'Ode to the Restoration of the Great Tang Dynasty' becomes more relatable," said Zeng Yucheng, a professor at Jingdezhen Ceramic University. "This ensures that the story of the Wuxi Stele Forest continues, allowing more people to discover its history and cultural significance."

Zhou Ping, president of Hunan Epigraphy Culture Research Association, agrees. "Cliff inscriptions hold immense historical, artistic, and scholarly value," he said. "Modern technology enables us to recover their voices, and share them widely."

The Wuxi project is now a key part of Hunan Province's cultural digitization strategy. "We want more people to connect with history," said Zhou Zhiyong, deputy director of the provincial Department of Culture and Tourism. "Digital tools are opening new pathways to do that."

This momentum is spreading well beyond Wuxi. The "SumHi" app, developed by a Hunan-based digital technology firm, functions like a 24-hour virtual museum. Users can explore digital replicas of national treasures -- from the Gansu Galloping Horse and the jade seal of Liu He, the Han-era Marquis of Haihun, to the sheer gauze robe from Mawangdui -- in hyper-detailed 3D, with textures and hues rendered more vividly than what the naked eye could perceive in person.

Beyond simply displaying artifacts, the platform is also piloting a new cultural access model, merging museum and creative industry resources into an open ecosystem where content creators can co-develop and share digital assets via smart contracts.

Such platforms are transforming how the public interacts with history.

"It felt like stepping into a scroll painting," said visitor Luo Wenjing, reflecting on her visit to Wuxi's digital museum during the Qingming holiday this spring.

"I'm bringing this home," she added, holding up a 3D-printed bookmark engraved with the phrase "Last for Thousands of Years," an excerpt taken from the final line of the "Ode to the Restoration of the Great Tang Dynasty."

"It's like carrying the spirit of Yuan Jie with me when I read." ■

This photo taken on Jan. 5, 2021 shows a view of the Wuxi Stele Forest in Yongzhou City, central China's Hunan Province. (Xinhua/Liu Wangmin)